| February 1, 2010

Framed "Pictures," Two Generations Apart

Fourscore and seven years ago (plus a

few months), a work of music came into being that quickly established itself as a staple

of the orchestral repertory, and indeed a showcase for the full-sized modern orchestra:

Ravel’s stunning orchestral setting of Mussorgsky’s piano suite Pictures at

an Exhibition. While the success of this version did stir up some interest in the

original one for piano, which had been generally neglected, more than a few music-oriented

souls even today regard the work as being essentially an orchestral one; some, in fact,

are surprised to learn that it was originally for piano solo. Fourscore and seven years ago (plus a

few months), a work of music came into being that quickly established itself as a staple

of the orchestral repertory, and indeed a showcase for the full-sized modern orchestra:

Ravel’s stunning orchestral setting of Mussorgsky’s piano suite Pictures at

an Exhibition. While the success of this version did stir up some interest in the

original one for piano, which had been generally neglected, more than a few music-oriented

souls even today regard the work as being essentially an orchestral one; some, in fact,

are surprised to learn that it was originally for piano solo.

As a matter of fact, this music’s "orchestral

character" was recognized by some of Mussorgsky’s own colleagues, from the time

the piano version was first published, in 1886, five years after his death. In that sense,

it is curious that Rimsky-Korsakov, who devoted himself to editing and orchestrating so

much of Mussorgsky’s music, did not orchestrate this work himself. But Ravel’s

version, commissioned by the legendary conductor Serge Koussevitzky and introduced by him

in Paris in October 1922, was neither the first nor the last. Rimsky-Korsakov, after

editing the piano score for its first publication, did have a hand in the production of

the first orchestral version: in 1891 he assigned the orchestration to his pupil Mikhail

Tushmalov, supervised Tushmalov’s work on it, and then conducted the premiere, in St

Petersburg.

Tushmalov’s version omits some of the work’s 16

sections, as do some of the subsequent editions. One of the most recent, though, created

by the Bulgarian pianist Emile Naoumoff and introduced by him with the National SO under

Mstislav Rostropovich in 1994, not only includes every section of the Pictures but

brings in material from other Mussorgsky works and is treated as a large-scale piano

concerto. Other recent versions include a chorus in one or more sections. The excellent

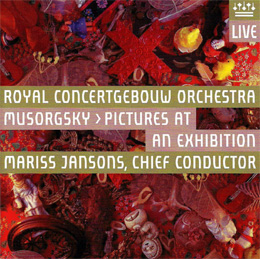

note by Michiel Cleij for the newest recording of the Ravel version -- with the Royal

Concertgebouw Orchestra of Amsterdam under its chief conductor Mariss Jansons, on the

orchestra’s own label (in SACD on RCO Live RCO 09004) -- advises that research by

David Raksin, an American composer remembered primarily for his film scores, showed no

fewer than 86 transcriptions for various forces -- orchestra, a cappella vocal

group, wind ensemble, organ solo, etc. -- and the list has grown since Raksin’s death

in 2004.

Modest Mussorgsky

|

During the last 20 years the conductor Leonard Slatkin,

alerted by the London-based musical gadfly Edward Johnson to the various orchestral

treatments of the Pictures, found about two dozen of them and drew individual

sections from many of them to produce two different composite versions, the second of

which he recently recorded with the Nashville SO (Naxos 8.570716). Some of the editions

represented in the Slatkin compilations have been recorded in full -- those by Leopold

Stokowski, Lucien Cailliet, Sergei Gorchakov, Henry Wood, Vladimir Ashkenazy, Leo Funtek,

Walter Goehr -- but Mr. Slatkin, who has recorded the Ravel version twice, continues to

perform it, in his own edition, which restores -- in an orchestration based on

Ravel’s treatment -- the sections Ravel omitted. He acknowledges it as the standard

version, as several of the earlier orchestrators have done. (Sir Henry Wood simply

withdrew his version after Ravel’s came out.) As it happens, it also bears a certain

historical significance, as the culmination of the rich Franco-Russian musical exchange

initiated by Berlioz’s second visit to Russia, in 1867.

Berlioz made that visit, in 1867, at the invitation of Mily

Balakirev, the leader of the group of nationalist composers known as "the Five,"

or "the Mighty Handful," to conduct concerts of his own music in Moscow and St

Petersburg, which set off productive responses from various Russian composers. In the

years that followed, musical contacts between the two countries became increasingly

frequent. Early in the 20th century the Russian impresario Sergei Diaghilev moved to Paris

and began commissioning new operas and ballets from both French and Russian composers.

Along the way he happened to put Stravinsky and Ravel together orchestrating music of

Mussorgsky. A few years after Diaghilev’s arrival, Koussevitzky settled in Paris, and

not only commissioned and introduced new works from composers in both countries, but set

up a publishing house for new Russian music. The Russian Revolution of 1917 triggered a

new influx of Russians into Paris, where visitors from other countries were as likely to

encounter their music as works of native Frenchmen.

Thus the stage was set for Ravel. It is pertinent to note

that before orchestrating this work Ravel had orchestrated some of Mussorgsky’s other

music for Diaghilev, and his friend M.D. Calvocoressi, one of Mussorgsky’s

biographers, had got him so interested in the Pictures that he determined to score

this work for orchestra, and took the initiative by simply asking Koussevitzky to

commission the project. Koussevitzky was of course delighted; he held exclusive rights to

the Ravel score for several years, and made the premiere recording of it in 1930;

virtually every other conductor active since then has had a go at it.

Eugene Ormandy made three recordings of the Ravel, after

recording the version Lucien Cailliet created for him upon his arrival in Philadelphia as

Stokowski’s successor. Stokowski himself, who recorded his own version three times,

occasionally performed Ravel’s, and recorded portions of it quite late in his life.

It was not by accident that this work was chosen for the recording that alerted the world

to the meaning of the term "high fidelity," the one made for Mercury by the

Chicago SO under Rafael Kubelík in 1951. Its release the following year led the New

York Times critic Howard Taubman to use the phrase "living presence," which

Mercury quickly adopted for the series of recordings it introduced. Since then, the

Chicago SO has recorded the Pictures five times in stereo, under as many

conductors, from Fritz Reiner to Neeme Järvi. The new recording from Amsterdam is the

fifth by the Concertgebouw Orchestra, also under as many different conductors.

For a work recorded as frequently as the Pictures,

it is daunting to think of picking the "best" one, or even the half-dozen

"best" ones, but the one with the Royal Philharmonic Orchestra under René

Leibowitz definitely commands attention, and grandly repays it. Leibowitz (1913-1972),

remembered for his authoritative writings on Schoenberg and his school, studied with

Schoenberg and Webern -- and also, significantly in the present context, with Ravel. (At

least one of the other orchestrators of the Pictures, Leonas Leonardi, also studied

briefly with Ravel.) Leibowitz was a prolific composer himself, and a truly remarkable

conductor. Among his recordings, which range from Gaîté Parisienne and La

Boutique fantasque to works of Schoenberg, Berg and Webern, his Beethoven Ninth, with

the same RPO as in the Pictures, is also one of the most persuasive ever given the

permanence of a recording.

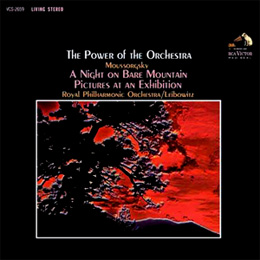

The Leibowitz Pictures,

which RCA recorded, together with Mussorgsky’s other well-known concert piece,

Night on Bald Mountain, for Reader’s Digest in 1962, found its way into

RCA’s own Living Stereo series, and had a subsequent LP reissue on Quintessence; it

has just appeared on CD for the first time -- remastered in SACD -- again with Night on

Bald Mountain preceding it. The insert cover is the original RCA cover art, including

the heading "The Power of the Orchestra," and RCA’s "Little

Nipper" and label style appear on the disc itself (Analogue Productions CAPC 2659

SA). The Leibowitz Pictures,

which RCA recorded, together with Mussorgsky’s other well-known concert piece,

Night on Bald Mountain, for Reader’s Digest in 1962, found its way into

RCA’s own Living Stereo series, and had a subsequent LP reissue on Quintessence; it

has just appeared on CD for the first time -- remastered in SACD -- again with Night on

Bald Mountain preceding it. The insert cover is the original RCA cover art, including

the heading "The Power of the Orchestra," and RCA’s "Little

Nipper" and label style appear on the disc itself (Analogue Productions CAPC 2659

SA).

Leibowitz’s performances of these two works suggest

the sort of insight and communicative power that perhaps could come only from a musician

with his background as a composer, conductor and scholar. While Ravel felt that he had

preserved the Russian character of the Pictures, several musicians have complained

that he did not, and this was the basic reason some of them undertook their own versions.

Leibowitz may be credited, though, with finding the "Russianness" underlying

Ravel’s transcription -- and doing so without downplaying or upsetting the overall

brilliance which only Ravel could have achieved.

For this recording, Leibowitz made his own edition of Night

on Bald Mountain, sifting through the various versions by the composer himself, the

now standard one by Rimsky-Korsakov, and other material. The version which his most

resembles is probably the one by Stokowski. Like Stokowski, Leibowitz ignored the fanfare

figure for trumpet introduced by Rimsky-Korsakov, but his score includes two competing

wind machines, among other touches.

It’s curious in a sense that both Leibowitz’s

48-year-old recording of the Pictures and the brand-new Jansons/Concertgebouw

(taken down live in concerts given in 2008) appear at the same time (and both in SACD).

Neither is especially generous in terms of playing time -- the two works on the Leibowitz

disc add up to 42.5 minutes, and Jansons’s 33-minute account of the Pictures

has the entire disc to itself -- but both qualify as parts of an elite handful of

recordings of the Pictures, despite occasional fluffs on the part of the RPO.

Possibly the budget for the original production limited retakes -- or perhaps Leibowitz

simply chose to forgo that option lest some of the spontaneity be lost.

That sense of spontaneity is one of the essential

differences between the Leibowitz and Jansons versions, but in general the various

contrasts are simply the sort of thing that makes it interesting to hear more than a

single version of such a familiar work -- and makes it inevitable that such powerhouse

orchestras as those of Chicago, Philadelphia and Amsterdam would record it so frequently.

The impact of the new Jansons is likely to be expressed along the lines of, "What a

marvelous orchestra!" -- while the Leibowitz is more likely to draw something like,

"What a fascinating piece of music!"

Both responses reflect

legitimate aims, impressively achieved. The Leibowitz was a demo LP when it first came

out, and it is still hugely effective sonically as well as musically. As in so many

instances in my experience with SACD reissues of early-stereo recordings, the SACD

remastering is OK, but the CD layer provides the spacious, well delineated impact, depth

and detail of the original LP -- and then some -- with a rich, vivid shine on the famous

RPO brass. The CD layer stunningly belies its age, making it again a candidate for top

honors. Both responses reflect

legitimate aims, impressively achieved. The Leibowitz was a demo LP when it first came

out, and it is still hugely effective sonically as well as musically. As in so many

instances in my experience with SACD reissues of early-stereo recordings, the SACD

remastering is OK, but the CD layer provides the spacious, well delineated impact, depth

and detail of the original LP -- and then some -- with a rich, vivid shine on the famous

RPO brass. The CD layer stunningly belies its age, making it again a candidate for top

honors.

If Leibowitz may be said to take us more deeply inside the

world of the composer Mussorgsky and his friend Viktor Hartmann, whose drawings,

paintings, architectural sketches and stage designs, shown in a memorial exhibition in

1874, following his death at the age of 39 the previous year, provided the impetus for the

work, it has to be acknowledged that Jansons’s richly gleaming performance is by no

means without character. If it is for the most part the character of a truly great

orchestra strutting its wonderful stuff, well, this is surely part of what Ravel had in

mind when he orchestrated the work, and the impact of the great Concertgebouw Orchestra

confidently digging in under the sure hand of Mariss Jansons provides not merely surface

brilliance but illuminating substance.

Since this is a production of the Concertgebouw Orchestra

itself, it goes without saying that the packaging and documentation are on the very

highest level. The sound captures the character of the orchestra splendidly. The

aforementioned note by Michiel Cleij (presented in English, French, German and Dutch) is a

model of how such things are done -- or ought to be done: richly informative, accurate in

every detail, eminently readable, and beautifully laid out. The one reservation here is

that the applause is left in at the end of the work, and for more than a few listeners

this can be a deal-breaker.

The mini-insert with the Analogue Productions disc

allocates only two pages to annotation (English only), and in that short space contains

enough errors to be an embarrassment. For instance: it is stated that Koussevitzky asked

Ravel to orchestrate the Pictures, but, as indicated above, the project came about

on Ravel’s own initiative: Koussevitzky provided the commission at Ravel’s

request. The premiere date in 1922 is given as May 3, but the actual date was October 19.

The listing of the section called "’Samuel’ Goldenberg and Schmuyle"

is hardly unique in omitting the quotation marks Mussorgsky placed around

"Samuel," but the commentary refers to "a drawing" of two

Polish Jews, and to "The picture" (singular), while these two figures were

actually portrayed individually by Hartmann, in two separate drawings. The two sections of

the "Catacombs" are run together without proper identification of the first

("Sepulchrum Romanum"). Nonetheless, the Leibowitz performances of the two

Mussorgsky works have so much character that this unexpected release is something to be

seized at once, before this treasurable recording disappears again, and probably for good.

. . . Richard Freed

richardf@ultraaudio.com

|