| October 1, 2009

The Solid and Timeless Charm of Chabrier, Plus More

Bicentenary Haydn Reissues

Constant Lambert’s book Music

Ho! (A Study of Music in Decline) remains in some respects as provocative now as when

it was first published, in 1934, when its author was turning 29. The book focuses

conspicuously on the works of Jean Sibelius, who was at that time just laying down his

pen, and also on an earlier composer too frequently dismissed as a lightweight, Alexis

Emmanuel Chabrier, who still needs -- and richly deserves -- some really strong advocacy. Constant Lambert’s book Music

Ho! (A Study of Music in Decline) remains in some respects as provocative now as when

it was first published, in 1934, when its author was turning 29. The book focuses

conspicuously on the works of Jean Sibelius, who was at that time just laying down his

pen, and also on an earlier composer too frequently dismissed as a lightweight, Alexis

Emmanuel Chabrier, who still needs -- and richly deserves -- some really strong advocacy.

"Above all," Lambert wrote, "Chabrier holds

one’s affection as the most genuinely French of all composers, the only writer to

give us in music the genial rich humanity, the inspired commonplace, the sunlit solidity

of the French genius that finds its greatest expression in the paintings of Manet and

Renoir [both friends of Chabrier]. There was, too, a touch of Toulouse-Lautrec about him

if we can imagine Toulouse-Lautrec without any of his sinister qualities.

"Although he unfortunately spent half his time trying

to become a French Wagner, his best work is a musical summing-up of the anti-Wagnerian

aesthetic which was not to find concrete verbal expression until much later -- in

Cocteau’s Coq et Arlequin. He was the first important composer since Mozart to

show that seriousness is not the same as solemnity, that profundity is not dependent upon

length, that wit is not always the same as buffoonery, and that frivolity and beauty are

not necessarily enemies."

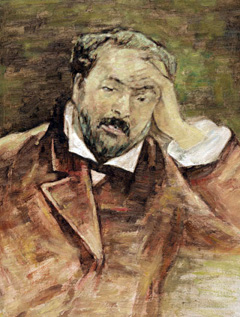

Chabrier (1841-1894) was possibly the

most remarkable French composer of his time in terms of sheer originality and of both the

breadth and the durability of his influence upon his latter-day compatriots. Like his

Russian contemporary Tchaikovsky, he was trained in law and did not take up a serious

career in music until he had held a minor post in a government ministry. Unlike

Tchaikovsky, who left his job in his early 20s to enter the St. Petersburg Conservatory

and upon graduation joined the faculty of the Moscow Conservatory (which now bears his

name), Chabrier didn’t give up his day job until he was nearly 40 years old. Chabrier (1841-1894) was possibly the

most remarkable French composer of his time in terms of sheer originality and of both the

breadth and the durability of his influence upon his latter-day compatriots. Like his

Russian contemporary Tchaikovsky, he was trained in law and did not take up a serious

career in music until he had held a minor post in a government ministry. Unlike

Tchaikovsky, who left his job in his early 20s to enter the St. Petersburg Conservatory

and upon graduation joined the faculty of the Moscow Conservatory (which now bears his

name), Chabrier didn’t give up his day job until he was nearly 40 years old.

In 1879, by which time he had established friendships with

eminent writers, painters and musicians and had become a significant figure in the

Société Nationale de Musique, Chabrier requested a leave from the Ministry of the

Interior to accompany his friend Henri Duparc (the composer of few but exquisite works, to

whom César Franck dedicated his famous Symphony in D minor) to Munich for a performance

of Tristan und Isolde. In the following year he left the Ministry to devote himself

entirely to music. His creative activity was cut off in 1892, when he suffered a general

paralysis; by the end of the following year his condition was such that he sat through the

Paris premiere of his opera Gwendoline without recognizing the music as his, and

nine months later he was dead. The works he composed within barely a dozen years, though,

constitute a pivotal factor in the renewal and continuity of French music.

That may seem an exaggerated claim on behalf of a composer

known to many people by a single work -- the brief orchestral rhapsody España --

and whom far too many others tend to put down as a mere concocter of light pieces. But the

aforementioned Gwendoline, a tragic work reflecting Chabrier’s early

fascination with Wagner, is not his only opera; his comic masterwork Le Roi malgré lui

("The King in Spite of Himself") is an absolute knockout. And when we do

have opportunities to hear his other works for orchestra, or for piano, the neglect they

have suffered over the years has to raise obvious questions.

Chabrier’s influence is easily

enough felt in various early works of Debussy, whose Petite Suite for piano duet

finds its antecedents in Chabrier’s orchestral Suite pastorale and the ten Pièces

pittoresques from among which its four sections were chosen. César Franck described

those piano pieces as "a bridge between our own times and those of Couperin and

Rameau." Ravel acknowledged that his famous Pavane pour une Infante défunte

was written "under the spell of Chabrier," and he produced a charming Gounod

paraphrase, À la manière de Chabrier. Chabrier’s influence is easily

enough felt in various early works of Debussy, whose Petite Suite for piano duet

finds its antecedents in Chabrier’s orchestral Suite pastorale and the ten Pièces

pittoresques from among which its four sections were chosen. César Franck described

those piano pieces as "a bridge between our own times and those of Couperin and

Rameau." Ravel acknowledged that his famous Pavane pour une Infante défunte

was written "under the spell of Chabrier," and he produced a charming Gounod

paraphrase, À la manière de Chabrier.

Erik Satie more or less inherited Chabrier’s style and

expanded on it; it was he who suggested that his own disciple Darius Milhaud compose

recitatives for Chabrier’s one-act opera Une Education manqué because, as

Milhaud recorded in his autobiography, his own music bore "the stamp of

Chabrier’s style." Francis Poulenc spoke of Chabrier as his "spiritual

grandfather." The list of such acknowledgements from latter-day French musicians is

virtually endless.

Apart from those acknowledgements, and the case made by

Lambert, there is the matter of charm -- a quality that cannot be manufactured or

faked or taught. For Chabrier it was instinctive and self-renewing, and for the listener

it can be reliably therapeutic. It would be lovely if our big orchestras were to perform

his music, beyond the occasional nod to España in a "family concert" or

"pops." The conductor Raymond Leppard became a hero of mine when he included the

Suite pastorale in his début concerts with the Chicago Symphony Orchestra, and the

great conductors of earlier eras were not reluctant to perform Chabrier: The legendary

Felix Mottl, who worked with Wagner and Bruckner, made brilliant orchestral arrangements

of Chabrier’s Bourrée fantasque and his four-hand Trois Valses romantiques;

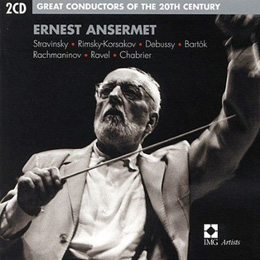

more recently, the formidable Ernest Ansermet showed his affection for Chabrier not only

in his performances and recordings, but also by naming his summer home "La

Chabrière."

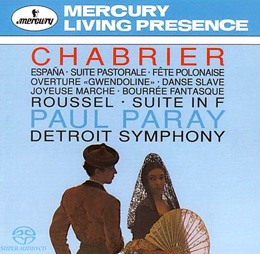

Ansermet and his French contemporary Paul Paray were among

the too few conductors who not only included Chabrier in their concerts but managed to

record more of his music than the obligatory España. Paray’s collection, with

the Detroit Symphony Orchestra, is still available, I believe, because it was one of Wilma

Cozart Fine’s wonderful Mercury reissues that were remastered for three-channel SACD

(475 6183). Copies of the earlier Redbook edition (434 303-2) are probably available, too.

The contents are: España; Suite pastorale; the two dance numbers

from Le Roi malgré lui (Danse slave and Fête polonaise); the Overture to Gwendoline;

Joyeuse Marche, and Bourrée fantasque -- with Roussel’s

Suite in F as filler.

Ansermet’s elegant Chabrier assortment, recorded in

1964, comprised España, Suite pastorale, Joyeuse Marche, and

the two dances from Le Roi malgré lui. It was reissued on CD in 1992, as part of a

12-disc Ansermet series in Decca’s Jubilee series (on the London label in the U.S.

at the time: 433 720-2, together with Lalo’s Norwegian Rhapsody, Scherzo for

Orchestra, and Overture to Le Roi d’Ys), and three years later, in somewhat

smoother sound if less lively in its detail, in the "Classic Sound" series (452

890-2, with César Franck’s tone poems Le Chasseur maudit and Les Éolides).

Neither of these two Decca CDs is in the current catalogue, and even

Universal’s Eloquence label, in Australia, in its otherwise remarkable Ansermet

series, has not revived these peerless performances, though Ansermet’s 1953

monophonic versions of the two most familiar Chabrier pieces are on an Eloquence disc

otherwise devoted to music of Saint-Saëns.

To my mind, Ansermet is simply the

most eloquent, insinuating and all-round persuasive conductor of this music, outshining

Paray and all the others who have recorded it. His account of the Fète polonaise

is simply stupendous: his tempo is broader than most, his accents and ritards

lending an infectious sense of spontaneity and utter intoxication without sacrificing a

whit of his customary elegance. Ditto for the Joyeuse Marche, and in fact for the

entire program, in which the only drawback is the inaudibility of the triangle in the

opening of the Suite pastorale. (Someone must have hit the thing, as there is a

conspicuous silence -- no music at all -- at that point.) To my mind, Ansermet is simply the

most eloquent, insinuating and all-round persuasive conductor of this music, outshining

Paray and all the others who have recorded it. His account of the Fète polonaise

is simply stupendous: his tempo is broader than most, his accents and ritards

lending an infectious sense of spontaneity and utter intoxication without sacrificing a

whit of his customary elegance. Ditto for the Joyeuse Marche, and in fact for the

entire program, in which the only drawback is the inaudibility of the triangle in the

opening of the Suite pastorale. (Someone must have hit the thing, as there is a

conspicuous silence -- no music at all -- at that point.)

But Paray on Mercury is indispensable for including the Bourrée

fantasque, and the peerless performance of the Roussel Suite -- and that elusive

triangle can be heard. As for duplicating, well, personally I am no more reluctant to the

idea of more than a single performance of a Chabrier program than to having more than a

single account of a Beethoven or Haydn symphony. But let me add here that if you

can’t find either of the Ansermet Deccas, you might look for his two-disc set in

EMI’s Great Conductors of the 20th Century series (7243 5 75094 2), which has that

incredible recording of the Fête polonaise as the final track, the true capstone,

even among works of Stravinsky, Rimsky-Korsakov, Debussy, Bartók and Ravel -- and

enhanced with a fuller and richer sound treatment than Decca managed for either of its own

CD reissues. The entire Great Conductors series has been discontinued, too, but copies are

bound to be around.

Another cut-out worth hunting for is the complete

performance of Le Roi malgré lui, with the Choeurs de Radio France and the

Nouvel Orchestre Philharmonique de Radio France, conducted by Charles Dutoit. This

was the only recording of the opera in its entirety, I believe, a two-disc set on the

Erato label, issued in 1985 (2292-45792-2) and out of print now for several years. It was

by no means a mere stopgap, but exhibited the vitality and refinement we associate with

this great conductor’s name. The cast, headed by the soprano Barbara Hendricks, the

tenor Peter Jeffes and the baritone Gino Quilico, is first-rate, and of course the Fête

polonaise makes a somewhat different kind of impression with the chorus participating.

The exemplary booklet included really valuable background as well as the full text in

French, English, and German. This is the sort of thing that ought never to go out of

circulation -- a prime example of the concept "collector’s item."

Amazon.com offers a few copies, at prices as high as $148.66; it’s time some

enterprising company got hold of this recording and made it available again at an

affordable price -- and time, too, for this work to enter the general operatic repertory.

This raises another obvious question:

Why hasn’t Decca recorded Dutoit in a program of orchestral Chabrier? Meanwhile,

there is a slighter but still very attractive Chabrier opera among EMI’s recent

reissues: L’Étoile, in the Opera de Lyon production under John Eliot

Gardiner, in a very attractive two-disc set (0946 3 58688 2) with lots of sparkle. No text

is provided, but there is a track-by-track description of the action and the music, and

the price is roughly 10% of what Amazon.com is asking for its hard-to-find Roi malgré

lui. This raises another obvious question:

Why hasn’t Decca recorded Dutoit in a program of orchestral Chabrier? Meanwhile,

there is a slighter but still very attractive Chabrier opera among EMI’s recent

reissues: L’Étoile, in the Opera de Lyon production under John Eliot

Gardiner, in a very attractive two-disc set (0946 3 58688 2) with lots of sparkle. No text

is provided, but there is a track-by-track description of the action and the music, and

the price is roughly 10% of what Amazon.com is asking for its hard-to-find Roi malgré

lui.

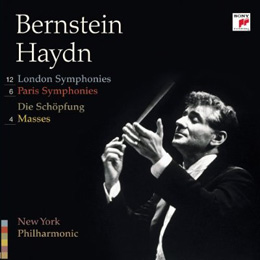

Meanwhile, too, the Haydn bicentenary rolls on, and Sony

has gathered all of its Haydn recordings under Leonard Bernstein in a single space-saving

12-disc box (88697 48045 2), which arrived just too late for inclusion in our recent

consideration of the same label’s recent restoration of George Szell’s set of

the first six of the London symphonies. Included are all six Paris symphonies, all 12

London symphonies, the Symphony No. 88 in G major, the oratorio The Creation, and

four of Haydn’s very greatest settings of the Roman Catholic Mass, all of which have

specific names: the "Mass in Time of War," the "Lord Nelson Mass," the

"Harmoniemesse," and the "Theresienmesse." The orchestra is the New

York Philharmonic in all these works except two of the Masses. The Westminster Choir sang

with the Philharmonic in three of the five choral works. The "Theresienmesse"

was recorded with the London Symphony Orchestra and Chorus, the "Mass in Time of

War" with a specially assembled orchestra and the Norman Scribner Chorus in

Washington, D.C. Among the fine soloists in the various works are such excellent singers

as Judith Raskin, Judith Blegen, Lucia Popp, Gwendolyn Killebrew, Frederica von Stade,

Rosalind Elias, Alexander Young, Robert Tear, Kenneth Riegel, Michael Devlin, Alan Titus,

John Reardon, Simon Estes, and Paul Hudson.

Of special interest here are the Paris symphonies and the

four Masses, which represent both Bernstein and Haydn at their formidable best. What is

more than a little disappointing is that Sony has failed to provide even the most basic

documentation. The thin booklet offers not a word of background on the music, and the

texts for the choral works are not included. Perhaps the text of the Mass is not

considered all that essential, but surely we need the words for The Creation; Sony

doesn’t even specify whether that work is sung in German or in English: the track

listing and labeling use German titles, and that is indeed the language that is sung. The

lack of information is especially regrettable in regard to the "Mass in Time of

War," because the performance that preceded this recording was itself a fascinating

moment in recent American history. Moreover, the cardboard gatefolds in which the discs

are encased present an annoying difficulty in getting them out without harming them or the

containers; individual sleeves, or even soft envelopes, would have been ever so much more

practical in this respect. I treasure this performance of the "Harmoniemesse,"

and this recording of the "Mass in Time of War," as already acknowledged, is a

document in its own right, but opportunities -- or, one might say, basic obligations --

were missed in this presentation.

. . . Richard Freed

richardf@ultraaudio.com

|