|

| August 1, 2007 An Honest Musician, a Glorious Ninth

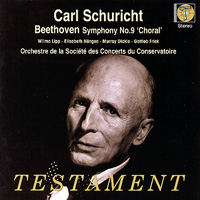

Schuricht’s musical sympathies were broad. Early in his career he championed Debussy, Delius and Stravinsky, and created the first Mahler Festival in Germany. He made few appearances in the US -- the St Louis SO in 1927, memorable Ravinia Festival concerts with the Chicago Symphony Orchestra in the early postwar years. He conducted concerts and recordings with the Berlin Philharmonic before he fled to Switzerland in 1944, but his reputation now rests mainly on recordings he made in the era of LP and stereo. His colleague Ernest Ansermet invited him frequently to conduct his Orchestre de la Suisse Romande, and he recorded for Decca with that orchestra as well as the Paris Conservatory Orchestra and the Vienna Philharmonic. He subsequently made some memorable recordings of Bruckner symphonies with the Philharmoniker for HMV, and recorded with some of the German radio orchestras for smaller labels. Several of Schuricht’s recordings have been revived on CD -- Decca, in fact, issued a five-disc set in its "Original Masters" series a few years ago -- but the Beethoven cycle he recorded with the Paris orchestra for HMV in 1957-58 was never issued in the US, or, for that matter, in Germany. The reason for this is given by Alan Sanders in his annotation for Testament’s recent release of the Ninth Symphony. The series was undertaken primarily for sales in France, capitalizing on the popularity Schuricht had developed in Paris. The French weren’t into stereo at that time, and several of the symphonies were recorded only monophonically. Only two of the symphonies appeared in the UK in HMV’s full-price line, and the rest came out there on Concert Classics, a low-priced label created at the end of the 1950s. The Ninth Symphony, however, was one of the few recorded in stereo, and for these sessions, in May 1958, HMV did not rely on the facilities available in Paris, but sent its own first-line production team and equipment from London. Victor Olof and Eric Macleod were the producers (Olof subsequently produced Schuricht’s splendid Bruckner Ninth in Vienna), and Christopher Parker was the engineer; as the Testament CD makes clear, their stereophonic recording of the Ninth turned out to be one of the most successful early-stereo efforts in continental Europe, its spaciousness and detail every bit a match and then some for what RCA Victor was doing in Chicago and Boston, and Decca in its familiar British and European haunts.

The splendid Brasseur Chorus must have been the match of any on earth in 1958, and the orchestra had by then forged a remarkable bond with Schuricht that meant it never gave less than its very best for him. The four solo singers, all stalwarts of the Vienna State Opera in the 1950s, could not have been better chosen. Both Wilma Lipp (the Queen of the Night in the first Karajan recording of The Magic Flute, Adele in the phenomenal Krauss Fledermaus) and Elisabeth Höngen had recorded the Ninth earlier with Jascha Horenstein on Vox, Höngen having recorded it earlier still with Furtwängler, Böhm and Karajan. Gottlob Frick was a renowned Sarastro, Daland and Wotan, while the Scottish tenor Murray Dickie made the first recording of the double-male version of Das Lied von der Erde (with Dietrich Fischer-Dieskau as fellow soloist, and the Philharmonia under Paul Kletzki). Frick’s presentation of the recitative introducing the "Ode to Joy" here is exactly the assuring benediction one wants to hear, and Dickie is convincingly "fuertrunken" on a similarly Olympian level in the exultant march episode. Best of all, no compromise or allowance need be made for the sound quality. Every word sung is intelligible, every aside and inner voice in the orchestra makes its presence felt. The documentation is at once comprehensive and concise, and the text is provided in a readable font. This is, in short, no mere curiosity, but in every respect a Beethoven Ninth to live with. ...Richard Freed

Ultra Audio is part of the SoundStage! Network. |

The German conductor Carl Schuricht

(1880-1967) was productively active until his death at age 86, but never enjoyed the level

of renown his musicianship ought to have brought him. He is frequently characterized as

"an honest musician," and may even have used that expression himself, for he

never regarded himself as being more important than the music he performed. The belated

arrival of his recording of Beethoven’s Ninth Symphony, made 49 years ago (and not in

one of the great bastions of German tradition, but in Paris), is as much a testament to

the enduring greatness of the work itself as to the stature of the conductor, and it

doesn’t hurt at all that the sound itself does not show its age.

The German conductor Carl Schuricht

(1880-1967) was productively active until his death at age 86, but never enjoyed the level

of renown his musicianship ought to have brought him. He is frequently characterized as

"an honest musician," and may even have used that expression himself, for he

never regarded himself as being more important than the music he performed. The belated

arrival of his recording of Beethoven’s Ninth Symphony, made 49 years ago (and not in

one of the great bastions of German tradition, but in Paris), is as much a testament to

the enduring greatness of the work itself as to the stature of the conductor, and it

doesn’t hurt at all that the sound itself does not show its age. But Testament has never been an

audiophile label, and the point of this release is not a "demo disc," but an

exceptional account of this venerated but also overexposed and frequently inflated work.

Schuricht, as "an honest musician," never allowed himself to get in the way of

the music. His approach was eminently straightforward and unfussy -- allowing a degree of

interpretive freedom, to be sure, but aimed at giving us the music’s own character

and its own natural momentum rather than driven by a determination to put his own stamp on

it. This account of the Ninth, truly exalted while not in the least

"monumentalized," reminds us why performances of this work used to be regarded

as special events. It is intensely communicative, superbly balanced, and so endearingly

unselfconscious that it is manages also to be a paragon of clarity without lapsing into an

antiseptic level of "objectivity."

But Testament has never been an

audiophile label, and the point of this release is not a "demo disc," but an

exceptional account of this venerated but also overexposed and frequently inflated work.

Schuricht, as "an honest musician," never allowed himself to get in the way of

the music. His approach was eminently straightforward and unfussy -- allowing a degree of

interpretive freedom, to be sure, but aimed at giving us the music’s own character

and its own natural momentum rather than driven by a determination to put his own stamp on

it. This account of the Ninth, truly exalted while not in the least

"monumentalized," reminds us why performances of this work used to be regarded

as special events. It is intensely communicative, superbly balanced, and so endearingly

unselfconscious that it is manages also to be a paragon of clarity without lapsing into an

antiseptic level of "objectivity."