|

|||

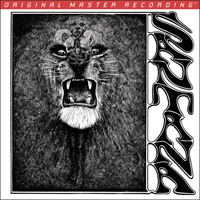

| April 1, 2008 Optimizing the Sound of the Song: Revisiting Vintage Santana in Many FormatsPrelude Almost everyone cultivates hobbies. Some like cameras, model airplanes, orchids, speedboats, sports cars. Those of us who are fond of high-end audio are inevitably driven by one common passion: We always want to hear more. However, when the hobby overlaps or merges with one’s profession, there may be a tendency for this passion to become a fetish. Born in Uruguay in 1942, Allan Russo occupied a special place in my space for over 25 years. We had been friends and professional colleagues since 1982, and I was deeply saddened by his recent and untimely passing. His ultimate portfolio was Caribbean and Latin American Sales Manager for Lenbrook International (NAD and PSB). Allan introduced me, a budding neophyte in consumer electronics, to Sumiko’s The Arm, designed by engineer David Fletcher, to be mounted on a first-generation Oracle Delphi turntable. I had bought the Delphi in Quebec from creative brothers Marcel and Jacques Riendeau, during a weeklong visit to their plant following the summer Consumer Electronics Show of that year. Allan then guided me to purchase a Mobile Fidelity Geodisc cartridge-alignment tool, and I have supported MoFi’s products ever since. He recently encouraged my acquisition of an NAD M5 SACD/CD player, which also includes Professor Keith O. Johnson’s revolutionary High Definition Compatible Digital (HDCD) decoding capability. Over the past few months, the M5 has breathed new life into my CD collection. It possesses the uncanny ability to engage and propel any audiophile to the threshold of the lunatic fringe. Over the years, Allan Russo continued to offer free technical advice about many of the other brand names with which my record label, Sanch Electronix Limited, inevitably became associated. These included AudioQuest, Carver, Classé, Krell, McIntosh, Nakamichi, Ortofon, PSB, Revox, VPI, et al. Therefore, I feel obliged to dedicate this article to him. Sowing a seed For some time, the gremlins have been haunting me to upgrade my reference playback system, whose main components have served me well and reliably for over a decade. I hasten to emphasize that the system is sonically transparent, capable of reproducing recorded performances with pristine, palpable, palatable precision. In short, nothing is conceivably wrong with it. Apart from being used for pleasure, the system’s main function is to evaluate the sonic quality of recordings. It also facilitates introducing my students to the intricate concepts of soundstaging and associated terms. This is one way of guaranteeing that they better understand and appreciate the idiosyncratic propensities of high-resolution audio. The acquired skills will enable them to meaningfully contribute to the further development and refinement of the art and science of recorded sound, which will undoubtedly redound to the benefit of future generations. How many people would complain about a Classé CP-60 preamplifier, CA-400 power amplifier, CDT-1 transport, DAC-1 converter, PSB Platinum T8 loudspeakers, and MIT interconnects? Yet the NAD M5 has been so revealing in its ability to resolve inner musical detail that it has whetted my appetite for more, and continues to meddle with my subconscious in real time. Evidently, the M5 has posed me the simple question "How much more can I hear?" Therefore, last September, I entered into dialogue with Andrew Payor about his Rockport Technologies Mira loudspeaker. This Select Component had recently been favorably reviewed by Jeff Fritz. Intuitively, I felt that the Miras would be a perfect match for Simaudio’s Evolution-series electronics, which I had been considering buying for some time. My mind was settled -- until I visited Ultra Audio’s website on New Year’s Day to discover that the Rockport Altair loudspeaker had been awarded Product of the Year status. With a mixture of impulsiveness, trepidation, and curiosity, I immediately contacted both Jeff Fritz and Andrew Payor to congratulate one and debrief the other. I even sent them copies of my latest HDCD releases, the Starlift Steel Orchestra’s Dance Again Mr. Bojangles and the Nite Life Caribbean Jazz Ensemble’s Midnight in St. James. Would they hear what I wanted them to hear? Would they hear more? Jeff’s kind reaction was to ask me to contribute a feature article to Ultra Audio. Andrew Payor is patiently waiting for the Almighty to send me money to purchase a pair of his speakers. Methodology Because high-resolution audio has been concurrently my hobby and my profession for more than a quarter of a century, I decided to conceptualize a project for Jeff that would encompass the realms of both the analog and digital domains. By the time Mobile Fidelity announced their reissue of Santana’s first two Latin-rock masterpieces, Santana (1970) and Abraxas (1971), on their Ultradisc II gold CDs, my project was crystallized. I would begin by using a VPI HW-16 record-cleaning machine to sterilize the surfaces of my carefully preserved vinyl copies of these albums, which were almost 40 years old. Information stored in their grooves would be subsequently transferred into the digital domain. For this I would use the aforementioned Oracle Delphi turntable with Koetsu Black and Ortofon Kontrapunkt moving-coil cartridges, one for each LP. Restoration of full 24-bit dynamics and digital remastering would be effected using a Microsoft HDCD Model One converter and Meyer Sound HD-I studio monitors. Finally, two reference CDs would be burned for evaluation and comparison with MoFi’s previous versions, remastered with MoFi’s Greater Ambient Information Network (GAIN2) and, before that, Sony’s Super Bit Mapping (SBM). I would therefore be able to review and evaluate four different formats and formulate an objective opinion. The exercise would be made even more interesting by the addition to my rig of an Audience aR6 line conditioner. En passant I have spent over 25 years of my professional life recording steelband music, mainly in Trinidad and Tobago, from very small groups to elephantine ensembles of 120 members. The latter, better known as steel orchestras, play very complex, extended arrangements of calypso compositions for the Panorama competition, held at Carnival time. Most of these outdoor recordings originate late at night, when creatures of the earth (crickets, frogs, etc.) have gone to bed. It always intrigues me to don a pair of Sennheiser HD 600 headphones, close my eyes, and monitor the live microphone feed emanating from various members of the percussion section, known as the engine room. Musicians are normally perched atop a large mobile rack, commonly called a float, positioned symmetrically about the remainder of the ensemble. There is usually some combination of trap set, cowbells, scratchers, congas, iron, tambourines, maracas, timbales, and whatever other paraphernalia arrangers may deem necessary to embellish their music. For example, they often employ tassa, djembe drums, bongos, timpani, gong, etc. Over the years, I have refined the art of delineating the position of each of these players and etching in my mind their exact locations relative to each other and the rest of the members of the various ensembles. I am very fond of percussion. Revelation

In each instance, the soundstage was huge, with an intimately intricate, delicately balanced perspective of depth, spaciousness, and reverberation. Instruments and voices floated in space, their images bending around the corners of the Platinum T8 speakers like rays of light through an optical diffraction grating. These were not merely recordings made at Fantasy Studios in California. Santana and his band were giving me the unique opportunity of a free high-energy concert in the midst of my living room! I perceived what sounded like sympathetic vibration of the cymbals at the introduction of "Waiting," during the conga solos. In a live recording, this may have easily been caused by movement of air from vibration of the conga skins. I cannot recall ever noticing it before. Maybe drummer Mike Shrieve was not holding the cymbals at the time to prevent this from occurring. Sometimes congueros use rubber-tipped mallets to play their instruments -- not so of Mike Carrabello and José Chepito Areas. You can actually sense the impact of human skin on animal skin, especially when they orchestrated their extended solos on "Jingo" and "Soul Sacrifice." (The vibrant call-and-response chanting of Babatunde Olatunji’s 1959 "Gin-Go-Low-Bah," from his very successful record Drums of Passion, evoked sensations of primal sensuality.) The visceral impact of the low-frequency content of Santana’s drumming was such that it caused my body to shudder. Amazingly, the system was so transparent that it afforded easy perception of the intertransient silence after the decay of each note of the cymbal crashes on "Shades of Time," from Santana. Because of the wider dynamic range, analog tape hiss was more pronounced on all CD recordings than on the vinyl. This was especially noticeable on the same album’s "Treat." I thought that if these recordings had been made in a more modern era, the vocals would have been focused around center stage, and would not sound as diffused as they do now. For me, Carlos Santana’s best guitar solo was on "You Just Don’t Care," on Santana. The electrifying fretwork of his nimble young fingers gave me goose pimples. Of course, the perennial favorite "Samba Pa Ti," from Abraxas, reminded me that the surest way to get couples to dance at parties in the 1970s was to play this track. I believe that this album’s "Oye Como Va," written by Tito Puente, is one of the few non-original compositions ever played by Santana. Rumor hath it that Carlos and Tito were related.

I cannot say with conviction that I preferred any one format to the other, although the MoFi and HDCD presentations were somehow more engaging. Perhaps this was because I am more familiar with their technologies. What would be really interesting is if I could obtain a Pacific Microsonics Model Two HDCD converter and original master tapes for production of a reference CD for comparison. My friend and mentor Paul Stubblebine would surely relish such a challenge. But even after several hours of repeated listening at high volume levels, I felt absolutely no sign of listener fatigue. I just wanted to hear more. On both Santana albums, three tracks segue from one to the next without pause. This leads me to the conceivable theory that part or all of both productions were live-to-two-track recordings. If I were to use one word to describe each album, I would say that Santana was seminal, while Abraxas is seductive. Conclusion High-resolution playback systems are primarily designed for listening pleasure and the enjoyment of true musical perspective and realism, especially from live recordings. Sensible upgrades to these systems usually allow one to hear more. This is why the proverbial audiophile is never satisfied, and always seeks new ways of tweaking a system to optimize its performance. This, in turn, propels the industry forward. Consider, for instance, what Mobile Fidelity has done to improve and preserve the sound of these two analog recordings from Santana. Their engineers have extracted every last nuance from the original master tapes by judicious, meticulous exploitation of modern proprietary technology. Similar compliments may be paid to companies such as Decca, Chesky, and JVC Extended Resolution Compact Disc (XRCD), all of which have successfully resurrected, remastered, and remarketed their back catalogs. It is interesting to note that there is currently a high global demand for these reissues. Consider also the resurgence of vinyl and the plethora of esoteric turntables and cartridges that have mushroomed in recent years. Is it because people are hearing more, or is it that the music of yesteryear is intrinsically more appealing? My hypothesis is that this was true of Caribbean genres in the main, but it seems that this trend may be worldwide.

I am particularly impressed by Jeremy R. Kipnis’s remastering of René Leibowitz and the Royal Philharmonic’s performances of Beethoven’s nine symphonies, released on five CDs by Chesky Records. These were originally recorded in the early 1960s by engineer Kenneth E. Wilkinson at Walthamstow Town Hall, London. Apparently, the London Underground passes beneath the venue, and a high-resolution system can allow one to occasionally feel a low-frequency flutter in the quieter passages of a few of these CDs as a subway train rumbles to its destination some 70 feet below street level. Talk about milking more out of recordings. My dream system -- my holy grail as of today -- will consist of a pair of Rockport Altair speakers, Simaudio Moon Evolution P-8 preamplifier and W-7m monoblocks, Kimber Select cables and interconnects, Microsoft HDCD Model Two converter, and the NAD M5 SACD/CD player. I doubt if there is a system on Earth (or Mars) that will allow me to hear anything but marginal differences in strengths and weaknesses when compared with this one. Will I then be satisfied forever? The answer is a resounding No! This is just human nature, I suppose. Meanwhile, I will have to be content with refining the art of listening to my current system while simultaneously hearing the one that I really want. In Trinidad and Tobago, this phenomenon is best described by the phrase having a Tabanca. I suppose that if we all did as I suggest, every high-end manufacturer would immediately go out of business. I occasionally peruse the early issues of Stereophile and The Abso!ute Sound stored in my archives. In those days, emphasis was commonly placed on guiding listeners to better understanding of high-resolution audio through forthright reviews. Advertising was restricted. Today, the industry has grown to gigabuck proportions. There are more new products to be reviewed than available magazine space and competent journalists to accommodate them. The result is that one sometimes becomes so engrossed in fanaticism that one stops listening to music and listens instead to cables, amplifiers, interconnects, line conditioners, and the like. Some of us would buy a system today and sell it three months later for half the price because of minuscule deficiencies that a reviewer has suddenly (conveniently?) unearthed. That is preposterous. Rest in peace, Allan, my brother, and continue to play sweet music for the angels. ...Simeon Louis Sandiford

Ultra Audio is part of the SoundStage! Network. |

From the opening bars of

"Waiting," on Santana, to the final strains of "El Nicoya," on Abraxas,

I psyched myself to concentrate on everything that Santana’s percussionists were

offering. I played each LP in turn through the phono input of the Classé preamplifier,

immediately followed by the Columbia Collector’s edition of Santana, then the

MoFi versions of both, and finally my own HDCD concoctions. I played music at levels loud

enough to ensure that my neighbors were edified, but comfortable enough to allow me to hear

more.

From the opening bars of

"Waiting," on Santana, to the final strains of "El Nicoya," on Abraxas,

I psyched myself to concentrate on everything that Santana’s percussionists were

offering. I played each LP in turn through the phono input of the Classé preamplifier,

immediately followed by the Columbia Collector’s edition of Santana, then the

MoFi versions of both, and finally my own HDCD concoctions. I played music at levels loud

enough to ensure that my neighbors were edified, but comfortable enough to allow me to hear

more. The timbales solo on "Se

a Cabo" is so gut-wrenching that it can stretch most power amplifiers to their limit.

I frequently use Abraxas’s "Black Magic Woman" (another rare Santana

cover, this one written by Fleetwood Mac’s Peter Green) and Santana’s

"Evil Ways" for audio demonstrations, and there is much to be gleaned from the

lyrics of both. The left, right, center, left timbales solo at the beginning of "Evil

Ways" created an illusion of a dormant volcano about to erupt.

The timbales solo on "Se

a Cabo" is so gut-wrenching that it can stretch most power amplifiers to their limit.

I frequently use Abraxas’s "Black Magic Woman" (another rare Santana

cover, this one written by Fleetwood Mac’s Peter Green) and Santana’s

"Evil Ways" for audio demonstrations, and there is much to be gleaned from the

lyrics of both. The left, right, center, left timbales solo at the beginning of "Evil

Ways" created an illusion of a dormant volcano about to erupt.